Surgical operations were something Africans did in the past but it looks as if history did not capture whether deliberately or indeliberately

Surgical operations, and other medical procedures carried out in early Africa were rarely recorded , and there is a likelihood that some procedures attributed to Western civilisation, originated from Africa.

The year was 1879, when R.W. Felkin, an English medical student, witnessed a Caesarean Section being carried out with great precision in Bunyoro Kingdom.

Felkin was a student when, after two years of medical study, he volunteered to go as a medical missionary to Uganda. He, however, found Buganda in a state turmoil , a situation that made him fear for his safety.

Luckily after a brief stay he bumped into three Baganda men who had been despatched by the King of Buganda as envoys to deliver a special message to Queen Victoria in England.

The three men helped Felkin find his way into Bunyoro Kingdom before they left him and continued with their journey to England. Unfortunately Felkin was arrested and detained at Katura by Bunyoro Kingdom’s law enforcers.

But this turned out to be a blessing in disguise for it was here that he witnessed a Caesarean Section being conducted by the natives much to his surprise.

In the village where he was detained, a woman went into labour.But despite Felkin’s medical knowledge, the villagers rejected his request to examine the patient. Instead a native doctor was called to deal with the situation.

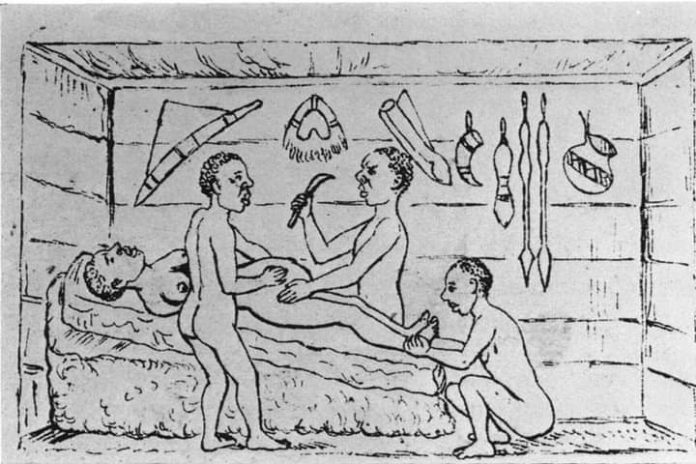

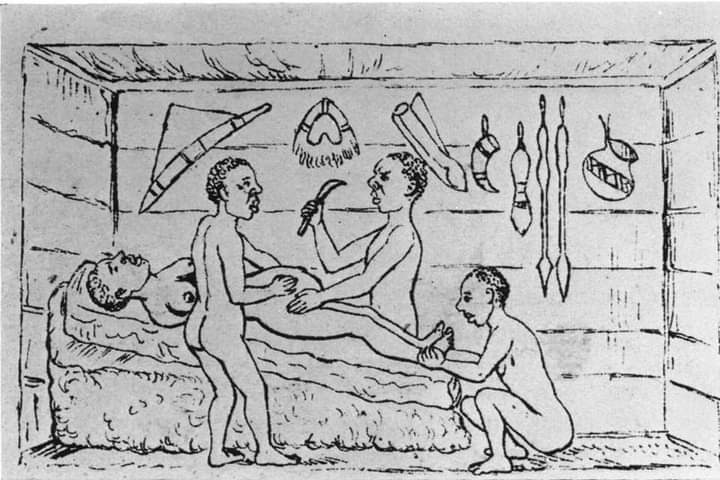

Felkin was however allowed to enter the hut where the native doctor was to carry out the surgical operation.

The patient was a healthy-looking woman about twenty years of age. She lay naked on an inclined bed, the head of which rested against the side of the hut. She was first anesthetized with Banana wine.

She was then tied down to the bed by bands of bark cloth over the thorax and thighs. Her ankles were held by a man squatting on his heels, while another man stood on her right side steadying the abdomen.

The native surgeon then held his knife high before chanting some words. He then washed his hands and cleaned the patient’s abdomen first with banana wine and then water.

The surgeon then made a shrill noise,which was repeated by the crowd waiting outside. He immediately made a quick cut upwards from just above the pubis to just below the umbilicus severing the whole abdominal wall and uterus so that amniotic fluid escaped.

During the process, the surgeon stopped bleeding in the abdomen by touching the bleeding points with red hot irons.The surgeon completed the uterine incision, the assistant helping by holding up the sides of abdominal wall with his hand and hooking two fingers into the uterus.

The child was removed, and the cord cut and the child was handed to an assistant. The operator then dropped his knife and squeezed the uterus with both hands, and he then dilated the cervix uterus from inside with his fingers.

He cleaned the clots and the placenta from the uterus while his assistant prevented the intestines escaping from the wound.The red hot irons were used to seal off some other bleeding points but Felkin noted specifically that they were used sparingly.

The uterus was squeezed till it contracted but was not sutured. A porous grass mat was now tightly secured over the wound and, the restraining hands being removed, the woman was turned over to the edge of the bed and then over the arm of the assistant so that any fluid in the abdominal cavity could drain away.

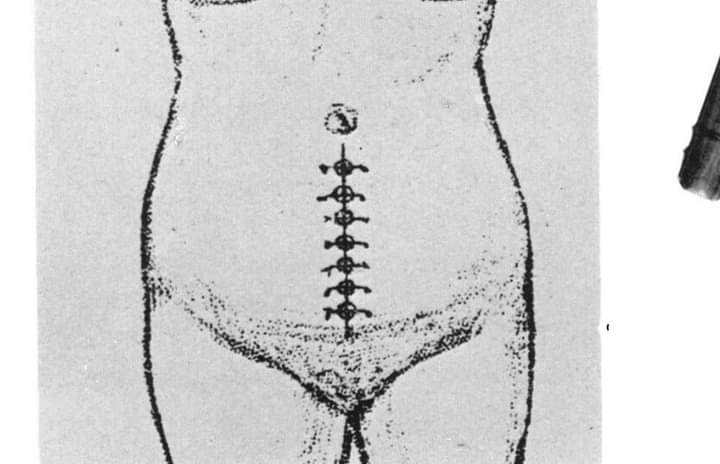

She was put back, the mat removed, and the peritoneal edges were held together and secured, together with the wound edges, by seven well-polished iron spikes which, after insertion, were tied together with skin. The patient, hitherto quiet, uttered a cry as the spikes were inserted.

A paste of pulped roots was plastered over the wound, covered with a banana leaf and finally a bandage of cloth was tightly applied thus completing the operation. Felkin was able to observe the progress of mother and child for eleven days.

The child had sustained a small cut on the shoulder which was dressed and was healed after four days. The fact that it was presumably a breech presentation may have been the indication for performing the operation.

During the recovery period Felkin also noted that the mother’s temperature rose on one occasion only. The uterine discharge was healthy but the milk supply was scanty.

On the third day the wound was dressed and one of the spikes pulled out, on the fifth day three were removed, the remainder on the sixth day. A fresh dressing was applied each time and a little pus was squeezed out.

Felkin could not continue his observations owing to his departure to England after his detention. He was so mesmerised that he bought the knife that had been used for the operation and took it with him to England. He had also made some sketches during the procedure.

In 1884 he narrated what he had seen in Bunyoro, in an address entitled ‘Notes on Labour in Central Africa’ given to Edinburgh Obstetrical Society in Scotland.

However his account was received with some scepticism which persisted for a very long time. “This is very startling indeed and a strange story indeed, almost too good to be true,” commented one Scottish doctor.

Nevertheless, the whole conduct of the operation as described by Felkin was evidence of a skilled, long-practised surgical team at work conducting a well-tried and familiar operation with smooth efficiency and unhurried skill.

Noteworthy was the use of banana wine, not merely for its stupefying anaesthetic properties, but for washing the patient’s abdomen and the surgeon’s hands. This was happening at a time when it was claimed that some surgeons in Europe only washed their hands after the operation.

By: Odhiambo Levin Opiyo